Using Special Purpose Credit Programs to Expand Equality

Lisa Rice, President & CEO, NFHA

- Special Purpose Credit Programs (SPCPs) are made available by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act.

- Building more affordable housing is important, but much more must be done to advance credit equity.

- Our markets are structurally unfair and we need intentionality to effectively address the racial wealth and homeownership gaps.

- SPCPs are an important tool in expanding fair access to credit, particularly for consumers and communities impacted by discrimination.

- SPCPs fulfill the letter and spirit of our nation’s fair housing and lending laws.

The COVID-19 health pandemic is the great revealer. It has exposed, in harsh reality, deep-seated inequalities that exist in our country built on centuries of unjust practices and policies, lack of enforcement of civil rights laws, and structural racism. People of color are disproportionately contracting and dying from the virus but they are also disproportionately experiencing housing eviction, overcrowding, and instability. This is, to a large extent, the result of residential segregation and the wide wealth and homeownership gaps between Whites and people of color. In fact, the Black-White homeownership rate gap, at a 30+ percentage point difference, is the largest it has been since 1890.[1]

But we have a unique opportunity to correct this disparity using one of our nation’s most promising civil rights laws – the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA). The statute allows institutions to develop Special Purpose Credit Programs (SPCPs), which provide a tailored way to meet special social needs and benefit economically disadvantaged groups, including groups that share a common characteristic such as race, national origin, or gender. Properly designed, SPCPs can play a critical role in promoting equity and inclusion, building wealth, and removing stubborn barriers that have contributed to financial inequities, housing instability, and residential segregation. SPCPs are also consistent with and provide a targeted and effective way to further the purposes of other civil rights laws, including the Fair Housing Act’s twin goals of overcoming discrimination and segregation.[2]

In fact, the Black-White homeownership rate gap, at a 30+ percentage point difference, is the largest it has been since 1890.

Building More Affordable Housing Won’t Cut It

While building more affordable housing will certainly help expand opportunities for underserved groups and is an important factor in the formula for reducing the racial homeownership gap, it is not a panacea and, without more intentional action, may ultimately do little to advance racial equity. The nation has a long history of investing in affordable housing programs that did little to advance opportunities for underserved groups.

Just before, during, and after WWII, the U.S. embarked on many bold and ambitious housing development projects that greatly expanded the number of affordable housing units for both rental homes and homeownership. But people of color were prevented from taking advantage of these opportunities. The programs were infected with racist policies that locked out Blacks and other people of color. Those policies created systems in the housing and finance sectors that are deeply inequitable, and we are still feeling their impacts today.

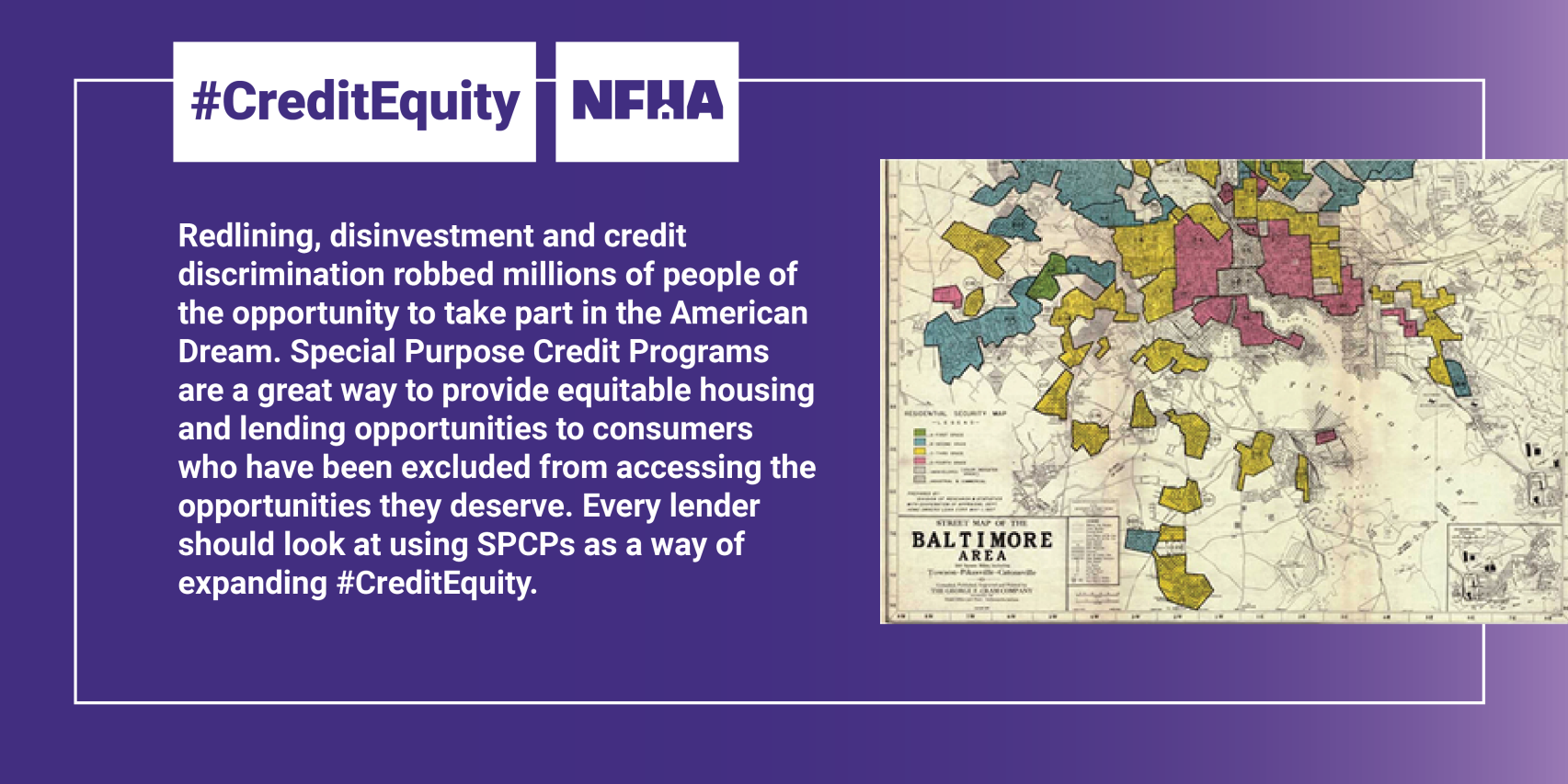

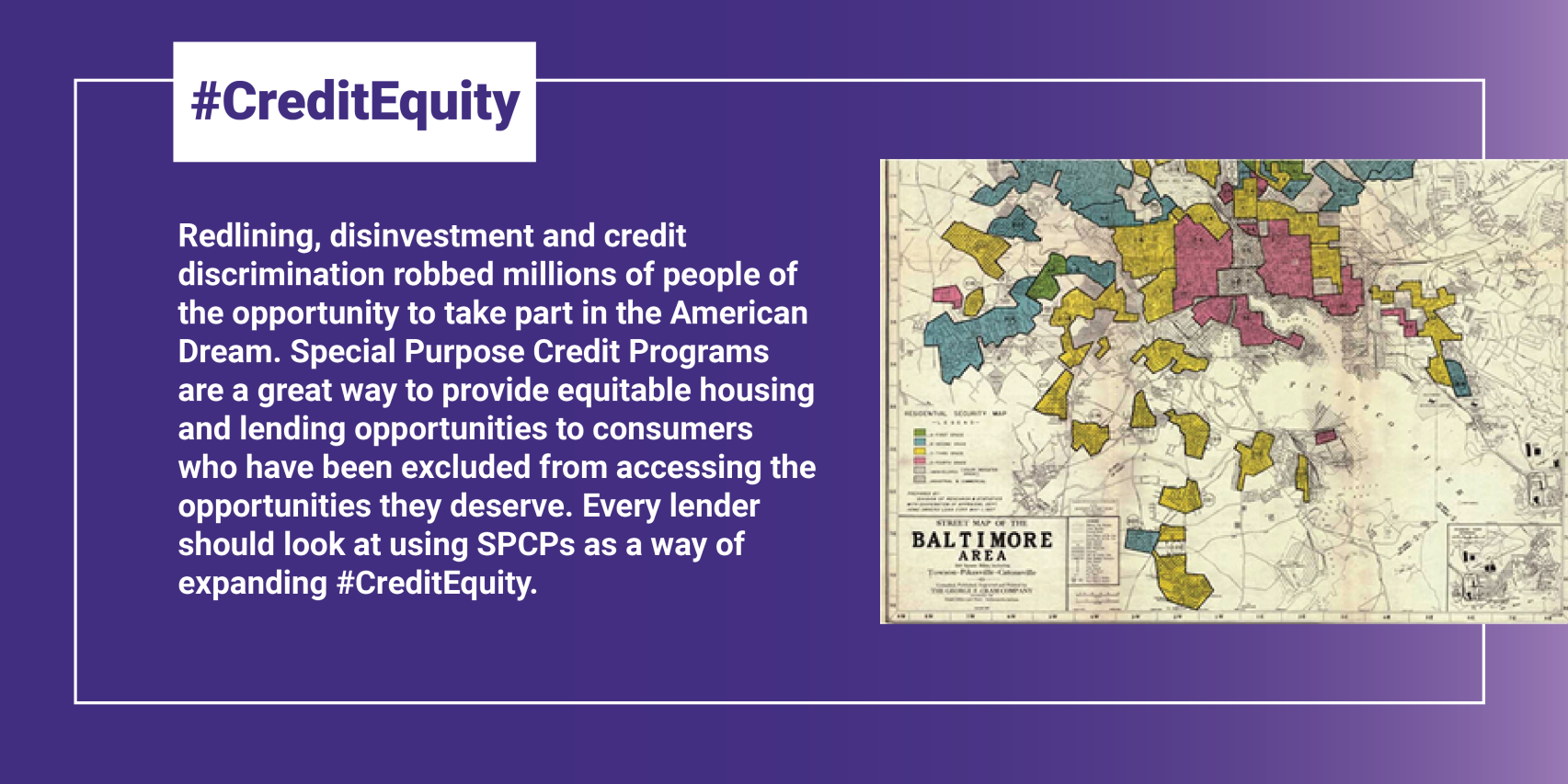

The nation’s largest affordable housing initiative was arguably the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage insurance program. It did very little to benefit people of color in the first decades of the effort largely because the guidelines and policies adopted by the program were designed to restrict access for Black people and other underserved groups.[3] Many of these policies were explicitly racist,[4] including the utilization of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s (HOLC) race-based redlining system, the requirement to use racially restrictive covenants, and language included in the FHA’s underwriting guidelines that associated risk with race.

Policies and practices in other federal programs also supported a separate and unequal housing market. For example, federal housing policies by the then US Housing Authority mandated residential segregation in publicly funded multi-family rental housing developments. Even today, some housing authorities still continue to practice segregation by offering facilities located in well-resourced neighborhoods to White tenants while steering Black tenants to complexes located in under-resourced areas.[5] Blatant discrimination in the implementation of the GI Bill,[6] the Social Security program, the National Highway Act, Urban Renewal Program, and more contributed to the permanent installation of a dual credit and housing market that too often prohibits consumers of color from accessing quality, sustainable credit options.

U.S. Financial and Housing Markets are Structurally Unfair

Inequity is baked into our housing and finance systems. It is a feature of the structures, not a bug; these systems were designed to be biased. Unfair policies were utilized for decades, creating clear and distinct advantages and support for White families, but not for others. These policies followed centuries of slavery, racial violence, and a race-based caste system that systematically robbed Blacks, Native Americans, Latinxs, and other people of color of opportunities to own homes, build wealth, and pass down assets to their heirs. Together, these practices denied people of color a chance to take hold of the American Dream of homeownership and other wealth-building opportunities, like starting businesses. And often when underserved groups have been able to access wealth-building opportunities, common injustices make the opportunities too short-lived.[7] The continued racial wealth and homeownership gaps are a testament to the reality that these systems are not fair. At the median, White households have eight times the wealth of Latinx families and ten times the wealth of Black families.[8] While 26 percent of White families receive an inheritance, only 8 percent of Black families receive one, and when Black families do inherit wealth, it is only 35 percent of what White families inherit.[9]

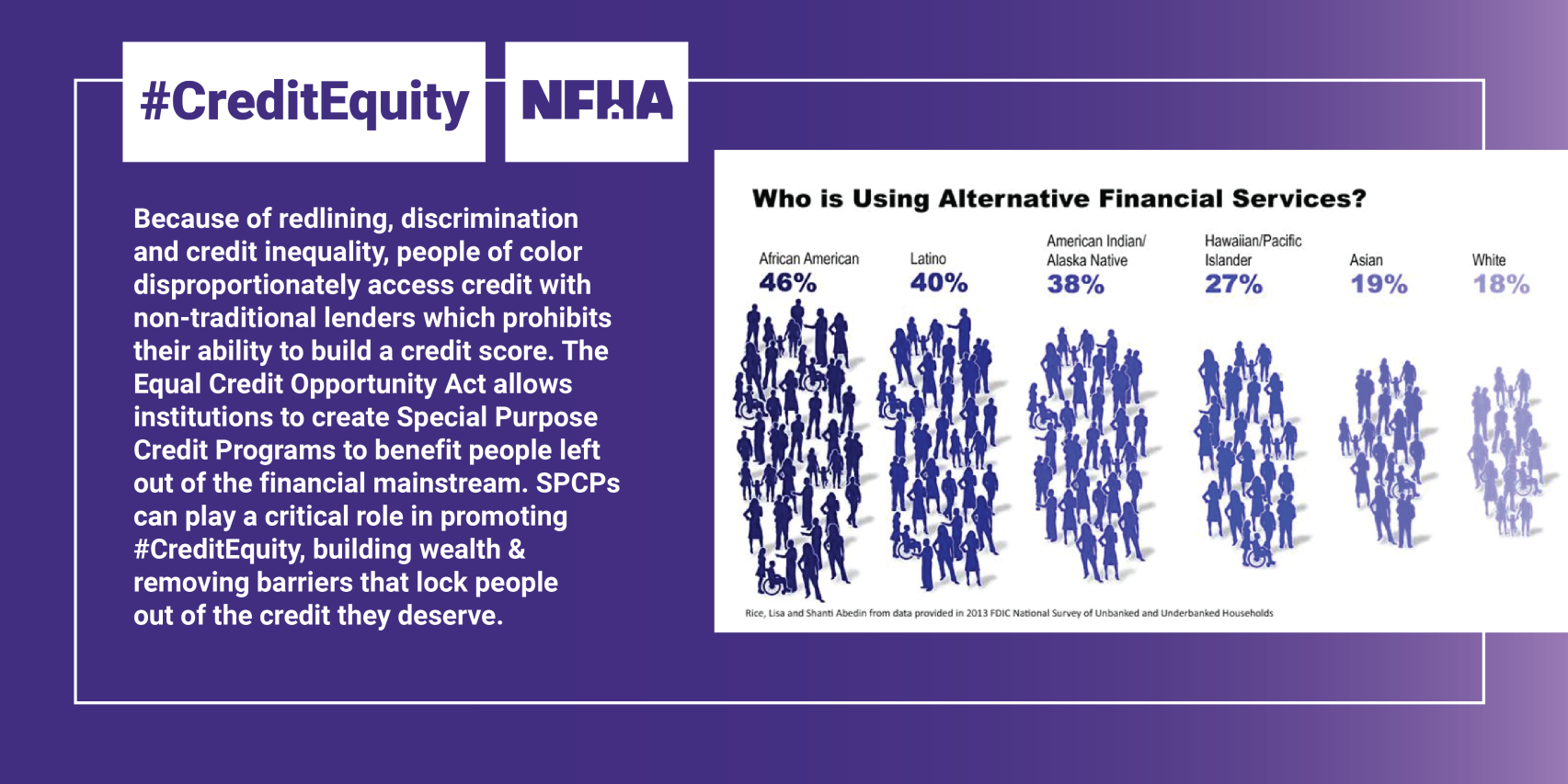

Today, while many policies and guidelines may not be explicitly discriminatory on their face, many generate widescale disparate outcomes based on race. For example, credit overlay policies, an over-reliance on outdated credit scoring systems and lending policies linked to debt-to-income ratios or loan-to-value ratios are all highly correlated to race and national origin and disproportionately disadvantage Latinxs, Native Americans, Blacks, and certain segments of the Asian-American and Pacific Islander populations. Algorithm-based systems, like automated underwriting systems and risk-based pricing systems, manifest and perpetuate these biases.[10] Our current financial system relies on assessments that can unfairly lock underserved groups out of the opportunity to access credit. For example, credit scores are a requirement for automated underwriting and risk-based pricing systems and matrices.[11] Yet roughly one-third of Black and Latinx borrowers don’t have credit scores[12] because they disproportionately access credit outside of the financial mainstream.

One of the reasons consumers of color disproportionately access credit through non-traditional credit providers (who typically do not report timely payments to the credit repositories) is because banks are sparsely located in Black and Brown communities. In fact, high-income Black neighborhoods are losing more bank branches than low-income non-Black areas.[13] An analysis by Standard & Poor found that between 2010 and 2018, majority-Black neighborhoods lost more branches than majority-White, Latinx, and Asian neighborhoods. Median household income did not help explain the pattern since majority-Black areas with median household incomes above $100,000 were as likely to not have a branch as low-income areas.[14]

However, many underserved consumers have nontraditional credit, like timely rental housing payments, or other compensating factors, like residual income, that soundly demonstrate their ability to pay a mortgage obligation. Moreover, the current system relies heavily on debt-to-income ratio requirements that disproportionately affect consumers of color. However, debt-to-income ratio requirements have been shown to be poor predictors of risk[15] – particularly for borrowers who are used to paying higher percentages of their income on rental housing payments. As a result, not only do these standards disadvantage borrowers of color, they are suboptimal for achieving their intended purpose of managing risk.

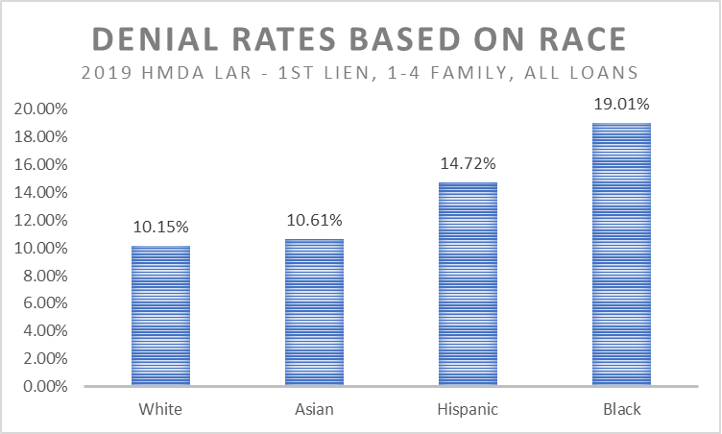

Because the U.S. lending and housing markets are so exclusionary, a disproportionate percentage of Black, Latinx, and Native American borrowers are turned down for mortgage credit each year. NFHA’s analysis of 2019 HMDA data reveals that Black applicants are denied for mortgage loans at almost twice the rate of White applicants. Latinx consumers are denied at almost 1.5 times the rate of White applicants. These trends have persisted over decades. (See chart below.)

Additionally, programs designed to extend credit to businesses owned by people of color have lackluster performance. The Paycheck Protection Program developed to help businesses impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic has provided minimal benefits to companies owned by Blacks and Latinxs. The Center for Responsible Lending estimated that during the first round of the PPP program, when support for small businesses was most critical, only about 5% of Black-owned and 9% of Latinx-owned businesses would be able to access the program.[16] Its projections were borne out. One analysis revealed that a disproportionate majority of PPP loans went to businesses in majority-White communities while a disproportionately small share of loans went to those located in majority-Black or majority-Latinx areas.[17]

Additionally, borrowers of credit face discriminatory roadblocks when trying to access car loans. An investigation by the National Fair Housing Alliance revealed that consumers of color with better financial profiles than their White counterparts were more often charged higher interest rates, received more costly options, presumed to be less qualified than they actually were, taken less seriously as buyers, and were more likely to be subjected to disrespectful treatment.[18] Sales people and finance officers at the dealerships where the investigations took place were much more likely to work with White consumers to bring prices down, sometimes through breaking policies, rules, and procedures or by making an extra effort to give the White consumer better pricing.[19]

In many respects the cards are stacked against underserved borrowers. Maintaining the status quo will never provide these families and consumers with the opportunities they need and deserve to access credit or secure housing stability. While building more affordable housing is critically necessary and may help expand equal housing opportunities, increasing affordable housing units alone will not address the racial inequality gap.

The Center for Responsible Lending estimated that during the first round of the PPP program, when support for small businesses was most critical, only about 5% of Black-owned and 9% of Latinx-owned businesses would be able to access the program.[16] Its projections were borne out.

We Need Intentionality in our Housing Policies and Programs

We are deluding ourselves if we believe we will cure centuries of race-based discrimination without targeted measures. A rising tide does not lift all boats, especially if some boats have holes and leak. And a rising tide can drown those who are not fortunate enough to have a boat at all. For too long, our housing and lending policies have primarily benefitted certain segments of our society – and that was by design. We must now be intentional and deliberate about expanding opportunities to those who were unfairly locked out. Because of our innately unfair structures and inequitable systems – residential segregation, dual credit market, over-reliance on outdated credit scoring systems, policies that favor wealthy households, etc. – maintaining the status quo will simply lead to more inequality. This observation is true even with respect to well-intentioned affordable housing programs. Without deliberate tailoring, these programs can exacerbate racial gaps—particularly in gentrifying areas—and can further segregation if housing options are limited to certain geographic areas.[20] We must implement policies and programs that serve as catalysts for change and are explicitly designed to bring opportunities to those who deserve but do not have them.

Our survival as a society depends on our planned and deliberate efforts to expand opportunities. Last month, Citi released a ground-breaking report, Closing the Racial Inequality Gaps, that conveyed a salient point sometimes missed when talking about racial inequality in the U.S. Systemic racism doesn’t just harm people of color, it harms our entire society. According to the report, if racial gaps in housing, employment, education, and investment had been closed 20 years ago, the U.S. economy would have increased by $16 trillion. Expanding fair access to credit would have added homeownership opportunities for almost 800,000 Black households, adding $218 billion in sales to the housing market. Providing equal lending opportunities to Black entrepreneurs would have added $13 trillion in business revenue and 6.1 million jobs per year. Closing these racial gaps today would add $5 trillion in GDP to the U.S. economy over a 5-year period.

Our society is becoming more diverse. Forty-four percent of the millennial cohort is comprised of people of color. The homebuyers of today and tomorrow are diverse consumers and if our housing and financial markets do not work for these consumers, not only will we unnecessarily harm people, we will stifle our economic growth and productivity. According to the Urban Institute, there are over 6 million millennials of color[21] who could qualify for a prime mortgage loan using responsible credit qualification standards. But these consumers are not participating in the market for myriad reasons, including policies that penalize borrowers who cannot afford a 20 percent down-payment or who cannot utilize their rental housing payment history to help them qualify for a loan.

Lenders Can Use Special Purpose Credit Programs to Expand Opportunity

Lenders have a real interest in meeting the credit needs of underserved communities, particularly if they want to meet their business objectives. Consumers of color, women, and other groups of underserved consumers represent the lion’s share of business growth opportunities today and in the future. Yet these consumers continue to face structural and other barriers that prohibit them from accessing the credit they deserve. SPCPs allow lenders to be intentional and specifically design programs to help underserved groups.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has promised steps to “help create real and sustainable changes in our financial system so that Blacks and other underserved groups have equal opportunities to build wealth and close the economic divide.”[22] To further that goal, it promoted the use of SPCPs, reminding creditors of the availability of these opportunities.[23] Historically, the CFPB has favorably highlighted SPCPs specially designed to serve businesses owned by people of color and to provide special purpose credit to historically underserved mortgage borrowers.[24]

ECOA allows both non-profit and for-profit organizations to utilize SPCPs to meet borrowers’ unique credit needs. Specifically, if a for-profit entity has determined that a SPCP would “benefit a class of people who would otherwise be denied credit or would receive it on less favorable terms,” the organization can create a program that meets certain qualifications, including:

- The program is established and administered pursuant to a written plan that identifies the class of persons that the program is designed to benefit and sets forth the procedures and standards for extending credit pursuant to the program; and

- The program is established and administered to extend credit to a class of persons who, under the organization’s customary standards of creditworthiness, probably would not receive such credit or would receive it on less favorable terms than are ordinarily available to other applicants applying to the organization for a similar type and amount of credit.

Lenders, non-profit organizations, and other entities have used SPCPs to expand credit access for underserved borrowers who can demonstrate they have an ability to repay their debt obligations but, due to exclusionary standards, structural barriers, and other hurdles, have been locked out of important opportunities they need to lead successful lives. Communities without credit are communities without hope and SPCPs are one way to bring hope back to neighborhoods that deserve fair access to financial investments. Lenders or other entities considering an SPCP should coordinate with their legal counsel to identify the appropriate steps that should be taken to establish a program. Legal counsel can also assist organizations in developing a written plan and strategy to meet the requirements set forth in ECOA. Institutions should confer with the CFPB and any other appropriate regulatory agency about plans to establish a SPCP.

Special Purpose Credit Programs Fulfill the Letter and Spirit of our Fair Lending Laws

The Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, and other fair housing laws, executive orders, and regulations are all designed to work hand-in-glove to advance equal and fair opportunities. Together, they provide an important bulwark to stop discrimination, dismantle inequitable structures, and promote policies, practices, and programs that help correct the horrible mistakes we have made in this nation – mistakes that still harm us today. They are designed to create a fairer society. The Fair Housing Act, a partial catalyst for Special Purpose Credit Programs, was passed just 7 days after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. President Johnson wanted to gift the Civil Rights Act of 1968 to the King family in memoriam to Dr. King for his valiant efforts to create a just and equitable society, his great sacrifice for this nation, and his vehement commitment to fair and open housing. Dr. King reminded us of the “interrelatedness of all communities and states” and that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act builds on the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fair Housing Act to further equity in our society and provide a more direct way for entities to advance fair housing goals. SPCPs can help further this nation’s commitment to fair housing and justice and aid in the fight to end discrimination and segregation. SPCPs can be a tool for tackling the racial wealth and homeownership gaps and ensuring that housing is genuinely fair, open, and available to all people. Just as we were purposeful and deliberate about excluding people of color, we need to be intentional about including them. SPCPs are an essential means of doing that. They are a great way for lenders to display their commitment to dismantling unfair systems and building programs and structures for advancing justice, fairness, and equality. They are a way for the financial services industry to step up and be a part of a long-needed solution to our nation’s history of structural racism and systemic bias.

Resources

- Read the Special Purpose Credit Program Toolkit developed by the National Fair Housing Alliance and Mortgage Bankers Association. The Toolkit was created in conjunction with the Homeownership Council of America.

- Read more about Special Purpose Credit Programs and how they advance the goals of fair housing laws like the Fair Housing Act.

- Read HUD’s Memorandum on the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity’s Statement on Special Purpose Credit Programs.

- Read HUD’s Legal Opinion which makes clear SPCPs that comply with ECOA and Reg B do not violate the Fair Housing Act.

- Read a special article by Chi Chi Wu of the National Consumer Law Center on Special Purpose Credit Programs.

- Read the article “The Use of Special Purpose Credit Programs to Promote Racial and Economic Equity” by two leaders in the CFPB’s Fair Lending Office – Patrice Ficklin, Fair Lending Director, and Charles Nier, Senior Fair Lending Counsel. The article is included in PRRAC’s May 2021 edition.

- Read important guidance from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau about Special Purpose Credit Programs.

- Read a CFPB blog on Special Purpose Credit Programs.

References

- Adam Levitin, “How to Start Closing the Racial Wealth Gap,” The American Prospect, June 17, 2020 https://prospect.org/economy/how-to-start-closing-the-racial-wealth-gap/

- Steve Hayes, “Special Purpose Credit Programs: How a Powerful Tool for Addressing Lending Disparities Fits Within the Antidiscrimination Law Ecosystem,” National Fair Housing Alliance, October 2020.

- Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017).

- Gregory Squires, The Fight for Fair Housing: Causes, Consequences, and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act (New York: Routledge, 2018). For a detailed explanation of how federal race-based housing and credit policies promoted inequality, see Chapter 6, entitled “The Fair Housing Act: A Tool for Expanding Access to Quality Credit.”

- Raisa Habersham, “Atlanta-based management companies face housing discrimination suit,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 20, 2020 https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-based-management-companies-faces-housing-discrimination-suit/VzX5hVxIQ1QnLezhsw2klI/

- Erin Blakemore, “How the GI Bill’s Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans,” History, June 21, 2019 https://www.history.com/news/gi-bill-black-wwii-veterans-benefits

- Rakesh Kochnar and Anthony Cilluffo, “How wealth inequality has changed in the U.S. since the Great Recession, by race, ethnicity and income,” Pew Research Center, November 1, 2017 https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/01/how-wealth-inequality-has-changed-in-the-u-s-since-the-great-recession-by-race-ethnicity-and-income/

- rymaine Lee, “A vast wealth gap driven by segregation, redlining, evictions, and exclusion, separates black and white America,” New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/racial-wealth-gap.html?mtrref=nationalfairhousing.org&gwh=3F6C5A39F6B7A11BB387A293FAECCE57&gwt=pay&assetType=PAYWALL

- Ruth Umoh, “How Closing the Racial Wealth Gap Helps The Economy,” Forbes, August 15, 2019 https://www.forbes.com/sites/ruthumoh/2019/08/15/how-closing-the-racial-wealth-gap-helps-the-economy/#101119847942

- Robert Bartlett, Adair Morse, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace, “Consumer-Lending Discrimination in the FinTech Era,” University of California, Berkeley, November 2019 https://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/morse/research/papers/discrim.pdf

- “Loan-Level Price Adjustment Matrix,” Fannie Mae, October 21, 2020 https://singlefamily.fanniemae.com/media/9391/display

- Jung Hyun Choi, Alanna McCargo, Michael Neal, Laurie Goodman, and Caitlin Young, “Explaining the Black-White Homeownership Gap: A Closer Look at Disparities Across Local Markets,” Urban Institute, October 2019 https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101160/explaining_the_black-white_homeownership_gap_a_closer_look_at_disparities_across_local_markets_0.pdf

- Zach Fox, Zain Tariq, Liz Thomas, and Ciaralou Palicpic, “Bank Branch Closures Take Greatest Toll on Majority-Black Areas,” S&P Global, July 25, 2019 https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/bank-branch-closures-take-greatest-toll-on-majority-black-areas-52872925

- Fox, “Bank Branch Closures Take Greatest Toll on Majority-Black Areas.”

- “NFHA Comments on the CFPB’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for the Qualified Mortgage Definition under the Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z)” National Fair Housing Alliance, September 16, 2019, https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/NFHA-QM-Comments-Final.pdf

- Tommy Beer, “Minority-Owned Small Businesses Struggle to Gain Equal Access to PPP Loan Money,” Forbes, May 18, 2020 https://www.forbes.com/sites/tommybeer/2020/05/18/minority-owned-small-businesses-struggle-to-gain-equal-access-to-ppp-loan-money/?sh=1ffc83165de3

- Jason Grotto, Zachary R. Midler, and Cedric Sam, “White America Got a Head Start on Small-Business Virus Relief,” Bloomberg, July 30, 2020 https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-ppp-racial-disparity/?sref=437r7DCu&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter_axiosmarkets&stream=business

- Lisa Rice and Erich Schwartz, Jr., “Discrimination When Buying a Car: How the Color of Your Skin Can Affect Your Car-Shopping Experience,” National Fair Housing Alliance, January 2018 https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Discrimination-When-Buying-a-Car-FINAL-1-11-2018.pdf

- Rice, “Discrimination When Buying a Car: How the Color of Your Skin Can Affect Your Car-Shopping Experience.”

- or a more detailed explanation of these issues, see Andre M. Perry and David Harshbarger, “America’s formerly redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to rectify them,” Brookings, October 14, 2019 https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions/

- Laurie Goodman, Alanna McCargo, Edward Golding, Bing Bai, and Sarah Strochak, “Barriers to Accessing Homeownership: Down Payment, Credit, and Affordability,” Urban Institute, September 2018 https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99028/barriers_to_accessing_homeownership_2018_4.pdf

- athleen L. Kraninger, “The Bureau is taking action to build a more inclusive financial system,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, July 28, 2020 https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/bureau-taking-action-build-more-inclusive-financial-system/

- Susan M. Bernard and Patrice Alexander Ficklin, “Expanding access to credit to underserved communities,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, July 31, 2020 https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/expanding-access-credit-underserved-communities/

- “Supervisory Highlights,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau no. 12 (2016): sec. 2.5.2 https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/Supervisory_Highlights_Issue_12.pdf

#CreditEquity Twitter Storm Toolkit

Special Purpose Credit Programs are allowable under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act and provide a way for financial institutions to meet the special credit needs of people who have been impacted by lending discrimination, systemic racism, and redlining.